Firth of Forth

| Firth of Forth | |

|---|---|

The Forth bridges looking northwest | |

| Location | Scotland, United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 56°04′30″N 3°45′00″W / 56.075°N 3.750°W |

| Basin countries | Scotland, United Kingdom |

| Designated | 30 October 2001 |

| Reference no. | 1111[1] |

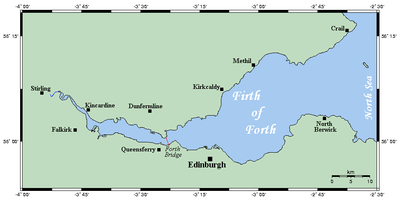

The Firth of Forth (Scottish Gaelic: Linne Foirthe) is the estuary, or firth, of several Scottish rivers including the River Forth. It meets the North Sea with Fife to its north and Lothian to its south.[2]

Name

[edit]Firth is a cognate of fjord, a Norse word meaning a narrow inlet.

Forth stems from the name of the river; this is *vo-rit-ia ('slow running') in Proto-Celtic, yielding Foirthe in Old Gaelic and Gweryd in Welsh.[3]

It was known as Bodotria in Roman times and was referred to as Βοδερία in Ptolemy's Geography. In the Norse sagas it was known as the Myrkvifiörd.[4] An early Welsh name is Merin Iodeo, or the 'sea of Iudeu'.[5]

Geography and geology

[edit]Geologically, the Firth of Forth is a fjord, formed by the Forth Glacier in the last glacial period.[6] The drainage basin for the Firth of Forth covers a wide geographic area including places as far from the shore as Ben Lomond, Cumbernauld, Harthill, Penicuik and the edges of Gleneagles Golf Course.[7]

Many towns line the shores, as well as the petrochemical complexes at Grangemouth, commercial docks at Leith, former oil rig construction yards at Methil, the ship breaking facility at Inverkeithing and the former naval dockyard at Rosyth, along with numerous other industrial areas, including the Forth Bridgehead area, encompassing Rosyth, Inverkeithing and the southern edge of Dunfermline, Burntisland, Kirkcaldy, Bo'ness and Leven.

Bridges

[edit]The firth is bridged in two areas. The Kincardine Bridge and the Clackmannanshire Bridge cross it at Kincardine, while further east the Forth Bridge, the Forth Road Bridge and the Queensferry Crossing cross from North Queensferry to South Queensferry.

History

[edit]The Romans reportedly made a bridge of around 900 boats, probably at South Queensferry.[8] The inner firth, located between the Kincardine and Forth bridges, has lost about half of its former intertidal area as a result of land reclamation, partly for agriculture, but mainly for industry and the large ash lagoons built to deposit spoil from the coal-fired Longannet Power Station near Kincardine. Historic villages line the Fife shoreline; Limekilns, Charlestown and Culross, established in the 6th century, where Saint Kentigern was born.

Construction of the Forth Bridge, a railway bridge, began in 1882 and it was opened on 4 March 1890 carrying the Edinburgh–Aberdeen line.[9]

The youngest person to swim across the Firth of Forth was 13-year-old Joseph Feeney, who accomplished the feat in 1933.[10] In October 1936, the Kincardine Bridge opened.[11]

On 4 September 1964, the Forth Road Bridge opened.[12] From 1964 to 1982, a tunnel existed under the Firth of Forth, dug by coal miners to link the Kinneil colliery on the south side of the Forth with the Valleyfield colliery on the north side. This is shown in the 1968 educational film Forth – Powerhouse for Industry.[13] The shafts leading into the tunnel were filled and capped with concrete when the tunnel was closed, and it is believed to have filled with water or collapsed in places.[14]

In January 1987, the first Loony Dook event took place and which now takes place annually, during which individuals dive or wade into the Forth on New Years Day.[15][16]

On 27 February 2001, a Shor 360 operated by the Scottish airline Loganair operating as Flight 670A ditched into the Firth of Forth after both of the plane's engines torque went to zero. After a mayday call was initiated the flight went into the water, all happening within the flight's phase of climbing to standard altitude. The only 2 occupants aboard - the captain and first officer, died in the accident. The crash was due to a lack of an established procedure for the flight crew to add engine air intake covers in adverse, windy, weather conditions. [17]

In July 2007, a hovercraft passenger service completed a two-week trial between Portobello, Edinburgh and Kirkcaldy, Fife. The trial of the service (marketed as "Forthfast") was hailed as a major operational success, with an average passenger load of 85 per cent.[18] It was estimated the service would decrease congestion for commuters on the Forth road and rail bridges by carrying about 870,000 passengers each year.[19] Despite its initial success, the project was cancelled in December 2011.[20]

In 2008, a controversial bid to allow oil transfer between ships in the firth was refused by Forth Ports. SPT Marine Services had asked permission to transfer 7.8 million tonnes of crude oil per year between tankers, but the proposals were met with determined opposition from conservation groups.[21] In November 2008, construction of the Clackmannanshire Bridge was completed and it opened to traffic.[22]

In 2011, construction of the Queensferry Crossing began and the bridge was formally opened on 4 September 2017.[23]

Ecology

[edit]The firth is important for nature conservation and is a Site of Special Scientific Interest. The Firth of Forth Islands SPA (Special Protection Area) is home to more than 90,000 breeding seabirds every year. There is a bird observatory on the Isle of May.[24] A series of sand and gravel banks in the approaches to the firth have since 2014 been designated as a Nature Conservation Marine Protected Area under the name Firth of Forth Banks Complex.[25][26]

The Forth was historically home to a large native population of European Oysters.[27] However, by the 1900s these had been fished to extinction in the Forth.[27] A project to introduce some 30,000 oysters back in the forth has been successful at re-establishing the population in the 21st century.[27][28]

Islands

[edit]- Bass Rock

- Craigleith

- Cramond

- Eyebroughy

- Fidra

- Inchcolm

- Inchgarvie

- Inchkeith

- Inchmickery with Cow and Calf

- Lamb

- Isle of May

Shoreline settlements

[edit]North shore

South shore

Places of interest

[edit]- Aberlady Bay, River Almond, Archerfield Links

- Barns Ness Lighthouse, Bass Rock and St Baldred's chapel, Belhaven, Blackness Castle

- Caves of Caiplie, Cockenzie Harbour, Cockenzie Power Station (site of), Cramond Beach, Culross

- Dalmeny House, Dirleton Castle

- River Esk

- Fidra Lighthouse, Fisherrow Harbour

- Gosford House, Granton Harbour, Gullane Bents

- Hopetoun House, Hopetoun Monument

- John Muir Country Park, John Muir Way

- River Leven, Longniddry Bents

- Musselburgh Racecourse

- Newhaven Harbour, North Berwick Golf Club, North Berwick Law

- Portobello Beach, Port Seton Harbour, Prestongrange Industrial Heritage Museum, Preston Tower

- Ravenscraig Castle, Royal Racing Yacht Bloodhound, Royal Yacht Britannia

- Scottish Fisheries Museum, Scottish Seabird Centre, Seton Sands, St. Fillan's Cave, St. Monans Windmill

- Tantallon Castle, Torness Nuclear Power Station, River Tyne

- Waterston House

- Yellowcraigs

References

[edit]- ^ "Firth of Forth". Ramsar Sites Information Service. Retrieved 25 April 2018.

- ^ "Forth area management plan 2010 – 2015" (PDF). SEPA. Retrieved 9 April 2017.

- ^ Field, John (1980). Place Names of Great Britain and Ireland. London: David & Charles. p. 74.

- ^ Anderson, Joseph; Hjaltalín, Jón A.; Goudie, Gilbert (3 January 1873). The Orkneyinga saga. Edinburgh: Edmonston and Douglas. Retrieved 3 January 2018 – via Internet Archive.

- ^ Fraser, James E. (2009). From Caledonia to Pictland: Scotland to 795. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. p. 171.

- ^ "Firth of Forth". landforms.eu. Archived from the original on 7 December 2019.

- ^ "No. 87 – The Firth of Forth" (PDF). Scottish Natural Heritage. Archived from the original (PDF) on 9 April 2017. Retrieved 8 April 2017.

- ^ Harrison, Jody (26 March 2018). "Secrets of the Romans' forgotten war against Scotland revealed". The Herald. Retrieved 22 May 2018.

- ^ "The history of the Forth Bridge, Fife". Network Rail. 25 September 2019. Retrieved 16 February 2025.

- ^ "Emma, 10, aims to break 84-year-old Forth swimming record". The Scotsman. Archived from the original on 20 September 2019. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ "Kincardine On Forth Bridge". Canmore. 21 February 1996. Retrieved 16 February 2025.

- ^ "Forth Road Bridge History". The Forth Bridges. 4 September 1964. Retrieved 16 February 2025.

- ^ Cooper, Henry (director). "Forth – Powerhouse for Industry". Moving Image Archive. Campbell Harper Films Ltd. Retrieved 15 May 2017.

- ^ Fraser MacDonald, "Scotland's secret tunnel under the Forth", The Guardian, 30 April 2014.

- ^ "Loony Dookers take the icy plunge". BBC NEWS. 1 January 2009. Retrieved 16 February 2025.

- ^ "Loony Dookers welcome the New Year with icy plunge". BBC News. 1 January 2025. Retrieved 16 February 2025.

- ^ "Accident description for Short SD3-60 registration G-BNMT". Aviation Safety Network. Retrieved 26 December 2024.

- ^ "Kirkcaldy-Edinburgh hovercraft trial". The Scottish Executive. 13 July 2007. Archived from the original on 17 November 2021. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ "Plans lodged for Forth hovercraft". Edinburgh Evening News. 7 January 2010. Retrieved 10 January 2010.

- ^ "Council 'killed off' hovercraft". 9 December 2011. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ "Forth oil transfer plan ruled out". BBC News. 1 February 2008. Retrieved 1 February 2008.

- ^ "10 years of the Clackmannanshire Bridge". Transport Scotland. 19 November 2008. Retrieved 16 February 2025.

- ^ Johnson, Simon (4 September 2017). "Queen opens new Forth crossing 53 years to the day after she opened old road bridge". The Telegraph. Retrieved 16 February 2025.

- ^ "Birding the Isle of May by Darren Hemsley". Scottish Ornithologists' Club. Retrieved 20 September 2019.

- ^ "Firth of Forth Banks Complex Marine Protected Area (MPA)" (PDF). Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ "SiteLink: Firth of Forth Banks Complex MPA(NC)". Scottish Natural Heritage. Retrieved 22 October 2019.

- ^ a b c Murray, Jessica (11 November 2024). "Oysters doing well in Firth of Forth after reintroduction, say experts". the Guardian. Retrieved 16 February 2025.

- ^ "Oysters reintroduced to Firth of Forth appear to be 'thriving'". Sky News. 11 November 2024. Retrieved 16 February 2025.

External links

[edit]- Isle of May bird observatory

- Forthfast experimental hovercraft service, 16–28 July 2007

- Inchcolm Virtual Tour a virtual tour around some of the Inchcolm's military defences

- Firth of Forth

- Estuaries of Scotland

- Landforms of Fife

- Firths of Scotland

- Bodies of water of Scotland

- Ramsar sites in Scotland

- Sites of Special Scientific Interest in Dunfermline and Kirkcaldy

- Sites of Special Scientific Interest in Edinburgh and West Lothian

- Sites of Special Scientific Interest in Falkirk and Clackmannan

- Sites of Special Scientific Interest in Mid and East Lothian

- Sites of Special Scientific Interest in North East Fife

- Bodies of water of the North Sea